Thoughtful generosity: strategic considerations for charitable giving Align your generosity with long-term goals Update by Felicia Chang, Head of Wealth Strategy

Update by Felicia Chang, Head of Wealth Strategy

31 January 2024

Many Westmount clients view charitable giving as an important part of their lives and legacies. Some enjoy the shared sense of purpose it gives their families to identify and support worthy causes. Others seek to repay the gratitude they feel toward academic or religious organizations that have been instrumental in their own lives. For others, the motivation is more personal and centered on meaningfully impacting people and causes that hold deep personal significance. As with most charitable decisions, there are factors to weigh regarding what, how, how much, and when to give. There are many ways for donors to give to charity; it is not one-size-fits-all. At Westmount, our charitable planning approach is structured around helping clients find an optimal strategy that yields the best result for their unique circumstances.

We spoke with our Director of Wealth Strategy, Felicia Chang, to learn about strategies for maximizing the impact of a gift—for both donors and recipients.

Felicia, are there any “up-front” considerations for clients who want to give to charitable organizations?

Yes. It depends on the type of asset the client is considering donating to charity. If the intent is to make significant gifts of cash or marketable securities, an up-front conversation with the recipient charity is likely not needed. That is unless the donors want something in return for their gift, such as naming rights on a building or program that might need to be negotiated.

However, if a client intends to donate property that is not cash or marketable securities, I would suggest they contact the intended recipient to ensure the charity is able to accept the gift. Some charitable organizations, for example, may not have the capacity to deal with non-cash assets, such as real estate, cryptocurrency, art, or collectibles.

We encourage any client contemplating a large charitable gift to speak with our team, so we can facilitate these discussions with the charity and streamline the process.

Presuming an organization can accept a gift, what’s next?

There are a few factors to keep in mind:

-

- Consider the intended scope of your donation. Can the organization use your gift in any way it desires, or do you want to limit your gift to a certain demographic, location, or cause? These specifications can often be negotiated and should be documented in writing.

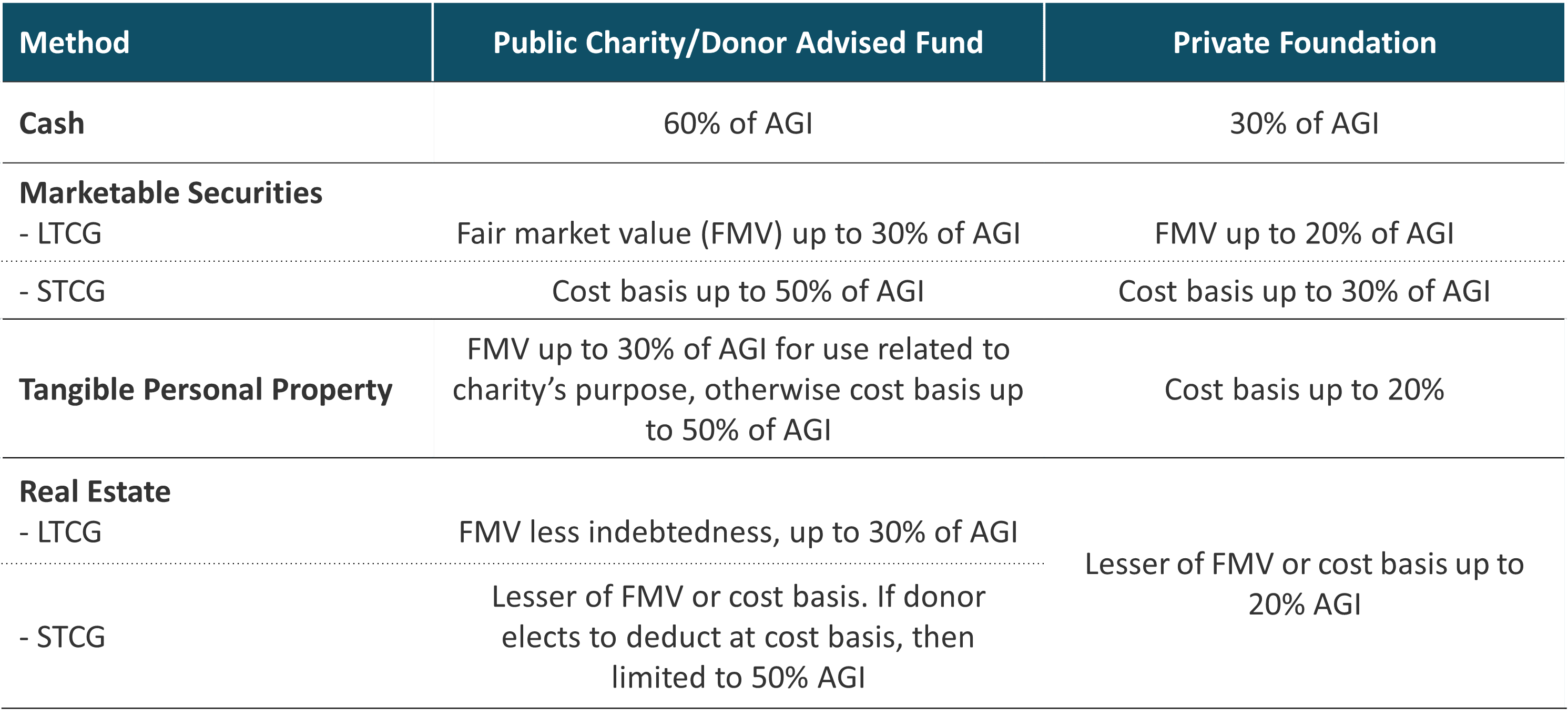

- The IRS limits charitable deductions based on the type of asset being gifted and the donor’s Annual Gross Income (AGI). Your accountant can clarify these limits and the potential “carry over” deductions for future years.

- The IRS also requires proof of charitable donations. It is important to obtain a contemporaneous written acknowledgment from the charity indicating the amount/value of the donated property, a description of any property other than cash contributed, and the value of any goods or services, if any, that organization provided in return for your donation.

- Gifts of certain assets over $5,000 require a qualified appraisal. In these instances, it can be akin to the phrase “it costs money to give money.”

What is AGI?

Your AGI, or Adjusted Gross Income, is your total income minus certain eligible deductions/adjustments to income. AGI is your starting point to determine your eligibility for certain tax credits and additional deductions to calculate your taxable income. How much you can deduct will depend on the type of assets you donate. Refer to the table below:

What types of assets can be gifted?

The “easiest” type of asset to gift is cash because there are no valuation concerns. The value of a $1,000 gift of cash is $1,000. However, this type of gift may not be the most efficient from a tax perspective.

A more advantageous option may be to donate highly appreciated stock. Gifting appreciated stock to charity effectively eliminates the capital gains tax the donors would incur if they were to sell the security themselves.

For example, if a donor purchased $300 worth of Amazon stock that is now worth $1,000, the value of the donated stock is $1,000, not the $300 basis. Donating that $1,000 worth of Amazon stock directly to the charity results in greater overall net value than if the donor had sold the stock and then made a cash donation. Charities are tax-exempt and do not pay any capital gains when they sell the stock, making this option very appealing to many of our clients.

How about non-traditional assets, like virtual currencies?

The rules for cryptocurrencies are different from those for cash because the IRS views cryptocurrencies as property—not securities. As a result, cryptocurrencies require a qualified appraisal to determine their fair market value.

To deduct that fair market value, a client needs to hold the cryptocurrency for more than one year. If held for less than one year, the deduction is limited to whichever is less: cost basis or fair market value.

How about collectibles, like art, watches, jewelry, or automobiles?

Clients can donate collectibles to charities. However, like cryptocurrencies, a client must have held the collectible for at least one year in order to maximize the deduction.

There are other caveats, too: first, the collectible must align with the organization’s mission—this is referred to as the “related use rule.” Next, the donor must hire a qualified appraiser to appraise the fair market value of the item; and last, the recipient must be a public charity and retain the item for at least three years.

If the charity sells the donated item within three years, the related use requirement will not be met, and the donor may have to amend their tax return limiting the deduction to the lesser of fair market value or basis.

Interestingly, if an artist donates work that the artist created, the deduction is limited to either the cost of materials or its fair market value—whichever is less.

What do you advise for privately held business owners? Can they donate business interests?

Yes. Any time that you’re considering the sale of your business, it’s critical to have these types of discussions very early on in the process so that you can have the broadest array of options available. Business interests are assets with complex tax implications for both the donor and receiving charity.

We will address this in more detail in a future Insights Lounge post, but in the meantime I would recommend that business owners broach the idea of gifting these interests with their Westmount advisor.

What about retirement accounts? Can I fund charitable bequests from my IRA?

For clients intending to leave a specific amount or percentage of their estate to charity, funding those gifts from their retirement plan assets can be a great option. IRAs are tax-inefficient vehicles because they may be subject to estate tax at the owner’s death and the beneficiaries pay income tax at ordinary rates when they receive the IRA distributions. Moreover, unlike other assets in the donor’s estate, assets held in retirement plans do not receive a basis adjustment at the owner’s death.

Conversely, charities do not pay any tax when they are designated as the beneficiaries of retirement plan assets. Donors also receive a dollar-for-dollar charitable deduction on the value of the donated IRA assets to offset any estate taxes due.

Is it true that The SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 impacted the scope of charitable donations?

Yes, SECURE 2.0 expanded the rules for Qualified Charitable Donations (QCDs), which allow clients to transfer funds from their IRAs directly to qualified charities. These QCDs can be used to satisfy a client’s Required Minimum Distribution (RMD), but do not provide a tax deduction (because they do not count as taxable income). Note the minimum age for an IRA RMD is now 73.1

Clients who are 70½ or older can use a QCD to donate up to $105,000 (indexed annually for inflation) to qualified charities directly from their IRA.2 Once a client reaches 73, these donations can be used to offset RMDs.

There are some guidelines to bear in mind: (1) the receiving organization must be a public charity – not a private foundation or a donor-advised fund; and (2) the distribution must be paid directly from the IRA to an eligible organization. Importantly, if the donor is 73 or older and wishes to offset an RMD with a QCD, these transactions must be carefully coordinated. These are not all the rules relating to QCDs, but they do provide a general overview of the strategy.

Any closing guidance?

Approach gifting thoughtfully and strategically so that your generosity aligns with your long-term goals. While gifting can involve some hurdles—from recordkeeping and paying for appraisals for IRS documentation—your generosity can heighten your impact and the personal satisfaction you derive from sharing your wealth.

As with any major financial decision, please consult your Westmount Advisor, who can help you navigate the various available charitable planning options. Call us at 310-556-2502 or email info@westmount.com to get started.

Recent posts

Sources

1,2As of Jan. 1, 2024

Disclosures

This document was prepared by Westmount Partners, LLC (“Westmount”). Westmount is registered as an investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Westmount believes the sources used in this document are reliable, but Westmount does not guarantee their accuracy. The information contained herein reflects subjective judgments, assumptions, and Westmount’s opinion on the date made and may change without notice. Westmount undertakes no obligation to update the contents of this document. It is for information purposes only and should not be used or construed as investment, legal or tax advice, nor as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. No part of this document may be copied in any form, by any means, or redistributed, published, circulated, or commercially exploited in any manner without Westmount’s prior written consent.